The 534 Club: Necessary Climb To Find Clean Water in Haiti

Water: The 534 Club

I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you will be clean… (Ezekiel 36:25).

Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink. (John 7:37)

I did it…I have joined the 534 club in Cange, Haiti. Actually…I walked these stairs twice. I was nervous traveling back to Cange to capture our water story. I was anxious; anxious that I would not be able to climb these steps given our last trip. These steps almost got the best of me.

The last time we were in Cange, Haiti…it was a scouting trip. We used the opportunity to walk the water system that Clemson Engineers helped build, harnessing the power of a natural spring to provide water to a village close to 800 feet above.

These steps were not always steps. This was a mountain path paved by dirt all the way down the mountain, leading the village to a natural spring with clean water. Local villagers would walk down this 800 foot drop with buckets to retrieve water for their families. The steps were eventually created and paved with concrete and rocks from the area, providing a clear path to the spring.

These steps are not like the steps we walk everyday. International building code says that steps should be no more than 7 inches (178mm) in height. I am not sure the Haitians followed this building code, because these steps are not only super steep, but also each step has to exceed 7 inches. This makes for a tough 534 step climb back to the top of the mountain.

The first time I walked these steps, I had no context behind the physical nature of traveling in Cange, Haiti.

Each time we traveled to Change Haiti, we would stay at the Zanmi Lasante compound. This compound was located in the center of Cange, with steps throughout requiring lots of climbing in-between buildings. Every meal requires you to climb 134 steps to be served a meal. To get to the spring where the water is pumped requires you to walk out of the compound, down the newly paved road roughly a half mile, then down 534 steps to the dam harnessing the water.

My friend/colleague/client David Lee who traveled with us said that he felt walking down the 534 steps was tougher than climbing back up. The impact on his knees made it tougher going down that going back up. Walking down these steps, carrying 15 pounds of camera gear will make your legs feel like jello. Now imagine spending a few hours capturing a story using lots of camera gear, running around the spring gathering footage, then packing up and walk back up the 534 steps. I was anxious.

This was the second time going down these steps, we knew what we were facing…so took our time. This time, we learned what it truly meant by the expression: “Haitian Time.” We brought light weight cameras, stabilizers, small drones, and light weight tripods to work and to capture all the imagery we needed. It took us over 2 hours to walk down, stoping at key points along the way to get our shots.

After getting to the bottom and capturing everything we need for our video story, it was time for a small lunch. A protein packed lunch providing energy to make the trek back up. The featured “Actor” is a Clemson Engineer, his name is Aaron Gordon. He stopped me before walking back up and gave me some advise, walk up the steps like the Haitians, follow their lead, embrace Haitian Time.

The power of the community, the power of connection. We slowly started to make our way up and I noticed Aaron and his Haitian friends would stop and talk, sharing jokes and stories in Creole. They would stop, talk, laugh, and keep on moving. Each stop was more than just talking, laughing, connecting; it was time to catch their breath in the 90 degree temperatures.

Many years ago when I began working with The Duke Endowment, I wanted to learn more about Mr. James Buchanan Duke’s (J.B.) vision through the Indenture of Trust, established with his initial gift of $40 million dollars, to harness the power of water to fund higher education, health care, the rural church, and child care.

J.B. and Ben Duke become intrigued by the potential of the fledgling hydroelectric power industry. The brothers acquire land and water rights along the Catawba River and build the Great Falls generating plant. In 1904 and 1905, Catawba Power Company and Southern Power Company (later Duke Power Company) are founded. The dividends from Southern Power Company provided the continual investment into The Duke Endowment. I have seen the impact of this investment daily here in South Carolina. Each hospital across the state has benefitted from The Duke Endowment grants, providing care for indigent patients.

James B. Duke writes on Page 23 in The Duke Endowment Indenture of Trust:

“For many years I have been engaged in the development of water powers in certain sections of the States of North Carolina and South Carolina. In my study of this subject I have observed how such utilization of a natural resource, which otherwise would run in waste to the sea and not remain and increase as a forest, both gives impetus to industrial life and provides a safe and enduring investment for capital. My ambition is that the revenues of such developments shall administer to the social welfare, as the operation of such developments is administering to the economic welfare, of the communities which they serve.”

And from Page 26:

“From the foregoing it will be seen that I have endeavored to make provision in some measure for the needs of mankind along physical, mental and spiritual lines, largely confining the benefactions to those sections served by these water power developments.”

J.B. and Ben Duke become intrigued by the potential of the fledgling hydroelectric power industry. The brothers acquire land and water rights along the Catawba River and build the Great Falls generating plant. In 1904 and 1905, Catawba Power Company and Southern Power Company (later Duke Power Company) are founded. The dividends from Southern Power Company provided the continual investment into The Duke Endowment. I have seen the impact of this investment daily here in South Carolina. Each hospital across the state has benefitted from The Duke Endowment grants, providing care for indigent patients.

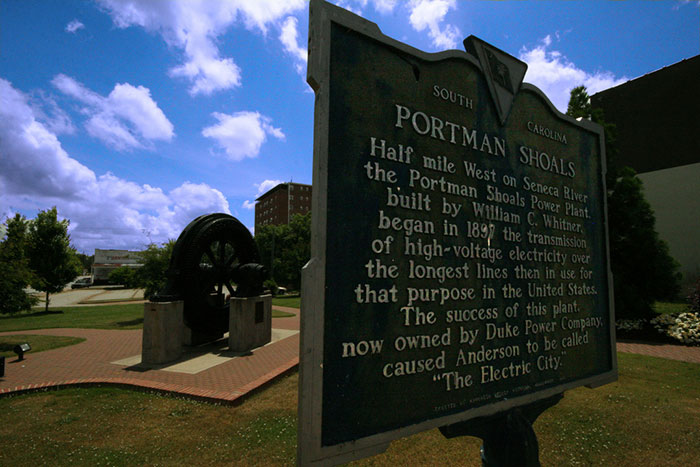

My hometown Anderson, SC is named the Electric City where the first long-line electrical transmission occurred. One of the original generators from this effort in Anderson is a monument today, owned by Southern Power Company. The impact of water has changed lives right here in South Carolina. I remind myself each time I produce another story of showcasing a grantee, if it was not for water…South Carolina would look and feel much different.

I am reminded by the work of The Duke Endowment as I stand an watch Clemson Engineers working along side the Haitian community. As they work on the dam that harnesses the power of the water, creating the right flow to run the turbines that pump water back to Cange’s water fountains. Clemson Engineers could have just come and built the dam, built the water filtration plant, run the pipe up the mountain, and walked away leaving the Haitian people to figure out how to manage.

Clemson Engineers were not only smart engineers with their knowledge and technical expertise, they understood the power of community. They knew if they worked with the Haitian people, taught them how to build the dam, install the turbines and the pumps, manage the filtration building, this partnership could build a longterm, sustainable approach to eradicating cholera from this village. They knew building community was vital, necessary, and the catalyst for a successful clean water plan.

After the water system was built in Bas Cange providing water to the village above, Cange has become one of the few areas of Haiti that has the lowest number of cholera cases in the country. Because of clean water in Cange, business have been built, local markets have thrived, schools have grown, health care has changed, and a mountain village is a thriving case study for Clemson Engineers.

It is so important to walk these steps, to carry the 20 pounds of gear up and down the 534 steps. We could have taken a bus to the bottom, found a boat, and made our way to the damn. But I knew we had to walk the steps, capture the story of the steps, feel the daily routine of water. I knew I had to feel the everyday rituals of the Haitians, to completely contextualize the experience, so I could in good conscience tell the story.

I learned how to walk the steps the second time. Instead of making a dashing sprint up the first 125 steps from Bas Cange, I walked in community. We took time, walking, climbing, stopping for conversation, laughter, and an opportunity to take in the view. Walking these steps is more than a physical and mental achievement, it is the vessel to see and feel the power of water.

Each day, I wake up and turn on the shower. I step into the flowing water, feeling the warm impact as it flows across my face. I turn on the faucet to clean my toothbrush before brushing my teeth. I fill up a cup for my daughter to drink. Water is a part of our everyday, utilitarian life in the United States of America. Clean water in Cange, Haiti is about community, connectivity, and opportunity.

As I make it to the top, walking the last few steps of the 534; I see one of the eight water fountains that provides the clean water harnessed below. A little boy is filling up his bucket to take back to his house. He has a bar of soap as he takes a bath after filling up his bucket. He opens his mouth and takes a sip, quenching his thirst on this hot, summer day. I am reminded, I am humbled, and I am thankful for this experience. I hope the Haitians feel like I have earned the right to join the 534 club.

***To learn more about the Cange Municipal Water Project & CDEC, go to: http://cedc.people.clemson.edu/